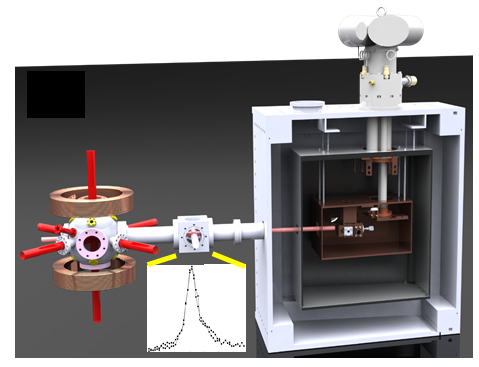

Matter near absolute zero has fascinating properties. Ultracold atoms and molecules can be confined in tiny regions of space and studied with great precision. At ZLab, we use laser light to create ultracold diatomic molecules of strontium. These molecules in an optical lattice allow us to measure subtle yet important properties of molecular quantum physics and chemistry. On a more fundamental level, the molecules provide an ensemble of tiny clocks where the vibrations determine the ticking rate. This type of quantum clock can help us test molecular quantum electrodynamics, the constancy of fundamental constants, and possible non-Newtonian forces at the nanometer scale.

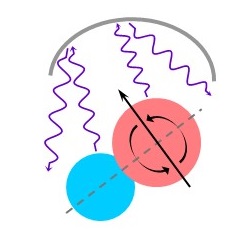

Ultracold polar molecules have many applications from modeling strongly interacting quantum systems to producing exotic atomic gases via dissociation. At ZLab, we are exploring ways to directly cool molecules in order to manipulate and study them. We use a combination of buffer gas cooling and laser cooling with the goal of creating a magneto-optical trap for a new type of diatomic molecule, barium monohydride. One exciting possibility is to precisely break the bond between the barium and hydrogen to obtain ultracold fragments. Dilute ultracold hydrogen would be the most fundamental atomic system for studying a wide range of fundamental physics.

We are collaborating with Yale University and University of Massachusetts to use cold diatomic molecules and optical techniques to measure time-reversal symmetry violation in atomic nuclei (Cold Molecule Nuclear Time Reversal Experiment, or CeNTREX). Recently, in collaboration with the Laboratory for Astrophysics we built an apparatus to quantify a tiny contamination of a noble-gas detector used in dark matter searches. In another interdisciplinary project, we used microcavities to stabilize lasers for next-generation portable atomic clocks.